Batching Cocktails

A few years ago, when I just getting into craft cocktails, I enrolled in an online bartender training program called BarSmarts. BarSmarts is a decent primer on distillation, spirits, and basic bartending techniques. I found it worth my time, even if I was a bit turned off by the obvious branding bias for Pernod Ricard products (Pernod created and runs the program). For those who graduate from the online course, Pernod offers a physical, traveling seminar series called BarSmarts Advanced in which industry veterans like Dale Degroff and David Wondrich travel from city to city and (supposedly) offer practical pointers on running a bar, advanced spirit identification and tasting techniques, and more in-depth content than that offered by the online course. My experience with BarSmarts Advanced was very disappointing. Very little of the seminar is devoted to practical learning, it’s mostly just a vehicle for the old timers to tell a few war stories of their time behind the stick and a way for Pernod Ricard to fleece you out of $75.

One of the not completely useless moments in the day was a question and answer session with the assembled panel. There were some legitimately good questions asked by my peers in the industry, many of which no doubt would have been addressed already had the seminar contained any meaningful content. One question, in particular, sticks out in my mind even today. A young man from the audience asked what roll, if any, batched cocktails should play in a bar program. It was interesting that all three of the panelists who answered were against pre-batching cocktails. They had various justifications for their stance but basically the animus was centered on the idea that it removes the technical expertise required of bartenders. Whether or not that’s true, its a pretty stupid reason for not using batches in your bar. Read on to find out why batching makes sense and how you can use it to increase guest satisfaction, lower costs, and drive profits.

Batched Cocktail Primer

When we talk about batching cocktails what we are describing is the process of combining the shelf stable ingredients in a given recipe together in a large mixing vessel, usually in large volumes and in fixed proportions that mirror those of the original cocktail. In my bar, I limit my definition of shelf-stable ingredients to commercially bottled spirits and liqueurs, bitters, and syrups that do not contain fruit. I’ll include fortified wines in batches if the overall ABV of the final batch will be over 24% (which is usually the case). I’ll include syrups that contain fruit (such as our house-made grenadine) if the overall ABV of the final batch is over 30%*. Cocktails can be batched in their entirety, or, for those cocktails that include citrus or cream, the shelf stable ingredients can be batched together and the mixers can be added to order. Take the Corpse Reviver #2, for example. I can batch the three shelf stable ingredients—gin, Cointreau, and Lillet Blanc—and add the lemon juice to order (I add the absinthe as a rinse to order as well).

To Batch or Not to Batch

Not every cocktail can—or should—be batched. Deciding which cocktails to batch is a balancing act between efficiency in the well while making drinks and efficiency in prep. Basically my decision to batch comes down to four things, how many bottles will I effectively remove from the well, how much money will I likely save, how much time will I save, and how much forgiveness does the cocktail have for flavor when free-poured. All four of these considerations relate directly to guest satisfaction.

The first one is an easy one, I have a finite amount of room for bottles in my service wells, and with 34 cocktails on each of my menus, I need to use that space as efficiently as possible. If a batch calls for four different spirituous ingredients, condensing them all into a single bottle potentially saves me three bottles worth of space. This allows me to fit more ingredients into each well and have a more diverse menu as well. More on this—and how a diverse menu leads to guest satisfaction—below. If a batch only calls for two ingredients, one of which is already in the well, then batching it doesn’t save me any space.

This leads to the second consideration, pour cost. I rarely batch only two ingredients together but if I have an expensive ingredient in a cocktail, I may batch the drink to reduce my pour costs, even if there are only two ingredients in the batch. I talk about this below. Lower costs allows me to keep our prices low, which increases guest satisfaction. On the other hand, batching two ingredients increases prep time and takes up storage space, so it may not be worth it if your cost savings on the batch is negligible.

Third, does it save my bartender’s time? The more complex the drink, the longer an unbatched version of it will take to properly construct, and the more time my bartenders save when using a batch. The faster my bartenders can make drinks, the faster our guests will receive them, which leads directly to guest satisfaction. I get into more detail on this below.

And finally, does the cocktail offer forgiveness when free-poured? We have a culture of free pouring many of our drinks. This may shock a lot of craft bartending purists but the reality is that free-pouring is a skill that can be learned like any other, and it can save you a ton of time in the well so your guests get their drinks faster. That said, some cocktails are more forgiving of slight (+/- ⅛) oz discrepancies in the recipe than others. If a cocktail is so noticeably off balance with slight errors in pour size that a guest would notice, I’m more likely to batch it.

Benefits of Batching

Increase Service Speed

One of the main benefits of batching complex cocktails is that service speed can be increased. I work in a large craft cocktail bar with 126 seats (103 of which are serviced by a single well). On a normal weekend night, the service well bartender makes an average of 736 drinks. We have several ways of managing that kind of volume efficiently, including the use of magnetic stir plates, a separate printer for wine and beer that is serviced by the barbacks, and two other wells used to service the guests sitting at the bar—the bartenders working those wells swing over to the service well and help out whenever they can. But it is an intense shift for the service well bartender who basically never stops making drinks from open to last call. One thing that saves a ton of time is having batches in the wells. Instead of having to pick up and measure out three or four spirits, a syrup, and two different bottles of bitters for a single cocktail, the bartender can simply measure out the full volume of the batch and be done with it. It’s a huge time saver that ensures our guests get their drinks as fast as possible, which makes them happier and more likely to return.

Increase Drink Consistency

Another benefit of batching is the fact that, because the ratios for a given drink are fixed in the bottle, it increases the consistency from one drink to the next. When dealing with small amounts like ¼ oz, it’s fairly easy for a bartender to accidentally overpour, especially when they’re moving fast. Having all your shelf stable ingredients pour out of the bottle at the same ratio means one measurement is all that’s needed to ensure that the shelf-stable components of a drink are balanced. More consistent drinks from one bartender to another, and from one drink to another by the same bartender, is another great way to increase guest satisfaction, and another huge benefit of batching.

Increase Menu Variety

My service wells have enough space to store 42 bottles. That sounds like a lot, but it’s amazing how quickly that space fills up when my average cocktail menu has 34 drinks on it. Some of those drinks might have five or six different shelf-stable ingredients in them. Without batching, it would be impossible for me to fit all the necessary ingredients into a well and still offer our guests the kind of diverse and deep menu our bar is known for. Consolidating three, four, or five different bottles into one is an obvious way of packing more ingredients into each well, allowing me free reign to add whatever I want to a menu, and making more of our guests happy about finding a cocktail that feels designed just for them.

Decrease Pour Costs

Batching cocktails reduces pour costs for three interrelated reasons.

First, it reduces the chances that your bartenders will overpour, both with respect to the individual ingredients within the recipe, and for the cocktail as a whole. For example, the Vieux Carré, a classic cocktail from New Orleans, requires 4 different spirituous ingredients and two different bottles of bitters. When measuring each of the spirits out individually it’s possible for a bartender to overpour any one—or multiple—of them. That’s four chances for a bartender working quickly to overpour slightly. It’s simple to do, especially when measuring scant volumes like ¼ ounce or even ½ ounce. The cost of even a 1/16 ounce overpour on one ingredient adds up when you’re making hundreds of cocktails a night, tens of thousands of cocktails per year. Over-pouring multiple ingredients (which heavy-fisted bartenders frequently do, compounds the cost even more and can throw the drink out of balance, resulting in a potential No-Like and a send back.

This leads us to the second way batches reduce pour costs: increasing consistency reduces send backs, this in turn reduces our “spillage” totals, which in turn reduces our overall pour costs.

Third, even if your bartenders do overpour slightly, the average cost to the bar of that overpour is reduced with a batch because the more expensive ingredients are mixed in with the cheaper ingredients. Let me give you a hypothetical example.

To set the stage, let’s pretend that a simple recipe calls for ½ ounce of Green Chartreuse and 1¼ ounces of well gin for the alcoholic ingredients (the non-alcoholic ingredients are not important). At the bar I run, I buy our well gin in ten-case drops, which allows me to realize steep discounts on the price down to $9.99/liter ($0.30/ounce). Buying Green Chartreuse by the case gets the price of a 750 mL bottle down to $48.49 ($1.91/ounce). If we were to batch these two ingredients into a single bottle, the cost per ounce of the batch, to the bar, would be $0.76.

So, a bartender working without a batch who accidentally overpours the Green Chartreuse by ⅛ of an ounce costs the bar $0.24. Conversely, that same bartender accidentally overpouring the batch by ⅛ of an ounce costs the bar only $0.10. “But what if the bartender overpours the gin instead of the Green Chartreuse in our unbatched version of the drink,” you may ask? “In that situation the ⅛ ounce overpour costs the bar only $0.04.” It’s true, in this scenario, overpouring the batch costs the bar more than an unbatched cocktail would have cost. There are three reasons that the batch will still save you money in the long run, but I’m going to save that for another post because this one is already going to be way too long.

I know talking in terms of savings of cents on the dollar may not seem like it’s worth it, but at a high-volume establishment making over 100,000 cocktails a year, those cents add up fast. I estimate that batching cocktails saves our bar around $11,750/year on costs eliminated by reducing overpouring (I’ll talk about how I calculate that figure in another post as well).

How to Calculate Batch Recipes

Now that we’ve covered the reasons for using batched cocktails in your bar, let’s get into the nitty gritty of how to do it properly. Calculating batch recipes isn’t difficult at all, but there are a few best practices that I’ve developed over time. The main thing to remember is that the batch has the exact same proportions as the original cocktail.

In America, most drink recipes are listed in fractions of imperial ounces, but bottles come in metric volumes of 750 mL or 1 liter. This could make for some tedious conversions between the two systems, but fortunately, the math is not necessary as all that matters is the proportions of one ingredient to another. Take a modern classic, the Black Manhattan, as a simple example. A fairly typical recipe (excluding the bitters) would be 2 ounces of bourbon and 1 ounce of Averna. Scaling up using a simple ratio of 1 ounce = 1 liter, our batch recipe would be 2 liters of bourbon and 1 liter of Averna. Scaling up further to maximize the size of a batch that will fit into one of our batch containers, our full recipe would be 14 liters of bourbon and 7 liters of Averna. This batch recipe is convenient for my bartenders who will be making the batch during their prep shift, as I get both our well bourbon and Averna from our distributors in liter bottles.

To minimize prep time spent on batches, I tend to calculate my batch recipes to be as large as possible but I’ve learned that maximizing the size of the batch isn’t nearly as important as making it easy to construct. This means that if a given recipe requires an ingredient that only comes in 750 mL bottles, I’ll try to create the recipe so that that ingredient is called for in a multiple of 750 mL. Take the Corpse Reviver #2 for example, a recipe that maximizes the size of the batch that would fit into one of our batch containers would be 7 liters of each ingredient, but because Lillet Blanc only comes in 750 mL bottles, I cap each ingredient at 6 liters (750 mL x 8 bottles = 6 liters). This makes each batch faster to construct and less prone to errors during construction, as well as making ordering and inventory easier for me.

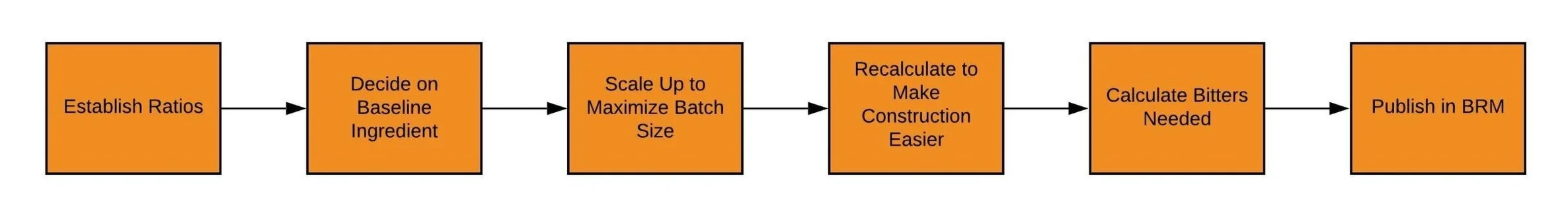

The process for creating a batch recipe is pretty simple. Start by figuring out the ratios of your ingredients. Decide on a baseline ingredient. Scale up to maximize your batch size. Resize batch if needed to ease construction. Calculate bitters volume. Publish the recipe in your BRM.

Batched cocktail design work flow

To make the following example more useful, I’m going to modify a classic cocktail recipe for the Vieux Carré to make it more complicated. We’ll use the following recipe:

Rye 1¼ oz, Cognac 1 oz, Sweet Vermouth ¾ oz, Benedictine ½ oz, Peychaud’s Bitters 3 dashes, Angostura Bitters 2 dashes

The first step is to establish the lowest common denominator (excluding the bitters). Here, we see that all of these ingredients can be broken down into ¼ oz parts. This lowest common denominator becomes the basis from which all the remaining volumes will be calculated. If we set ¼ oz equal to 1 liter, we get the following bitterless batch recipe:

Rye 5 liters, Cognac 4 liters, Sweet Vermouth 3 liters, and Benedictine 2 liters

This gives me a total batch size of 14 liters plus the volume of the bitters I still need to calculate. The recipe would work just fine, but for my purposes, I want to tweak it a bit to increase the overall batch size and also to better account for the size of the bottles I’m using in the batch. I get rye and cognac in 750 mL bottles and sweet vermouth and benedictine in liter bottles. That means for the current recipe I need 6⅔ bottles of rye and 5⅓ bottles of cognac.

I usually estimate my max batch size at around 21 liters, so I could potentially increase the batch size by up to 50%. If I reset ¼ oz to 1500 mL, my new batch recipe would be:

Rye 7500 mL, Cognac 6 liters, Sweet Vermouth 4500 mL, and Benedictine 3 liters

I like this recipe better because it maximizes the size of the batch I can fit into one of my batch containers and because it means that I have a partial bottle on only one ingredient instead of two, making it easier for my bartenders to construct and making it less likely that an error will be made when constructing a batch.

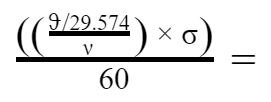

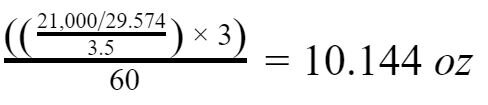

The final step in determining a batch recipe is to calculate the amount of bitters to include in the batch. This is a major hangup for a lot of people because normally the volume of bitters in a given cocktail is so small that they don’t know where to start when trying to figure out how to scale it up. For the longest time, I took a trial and error approach to this as well but in the last several years I’ve figured out a better way. My revelation came from determining the number of dashes of bitters in an ounce. Through dozens of tests I determined that the average number of dashes in an ounce is 60. This gave me the following equation to calculate the volume of bitters in a batch. Here, ϑ is the total volume of the batch in milliliters, excluding bitters, 29.574 is a conversion factor to convert from metric milliliters to imperial ounces, ν is the volume of the batch that is in a single cocktail, in ounces, σ is the number of dashes of bitters in each cocktail, and 60 is the number of dashes of bitters in an ounce.

So, let’s calculate the amount of Peychaud’s bitters required for our batched Vieux Carré above. Our total batch volume is 21,000 milliliters and the volume of the batch required for each cocktail is 3½ oz. This gives us a required volume of 10.144 oz of Peychaud’s bitters. I usually round down to the nearest ⅛ of an ounce, giving me a total required volume of Peychaud’s bitters of 10⅛ oz. The amount of Angostura bitters required in the batch is ⅔ that of the Peychaud’s, giving me a total required volume of Angostura bitters of 6¾ oz.

To make it easier to calculate bitters volumes in batches, I’ve made an excel spreadsheet, which I’ve converted into an online calculator for you to use for all your batching needs. I hope you find it useful.

Calculating Batch ABV

I don’t always calculate a batch’s ABV but if I’m ever concerned that an ingredient I’m including in a batch may spoil, I double check to make sure that the ABV is high enough to limit bacterial growth. Double checking batch ABV, coupled with proper batch storage (see below) and proper product rotation procedures (see this post), ensures that the drinks I’m serving my guests are not only delicious, but also fresh and safe to consume.

Calculating a batch’s ABV is simple to do. You simply multiply the volume of each of your ingredients by their respective alcohol content (ABV) expressed as a fraction (i.e. 35% ABV = 0.35), add those numbers up and then divide the sum by the total volume of the batch. Then multiply the result by 100 to get a value expressed as a percentage. If that didn’t make sense, perhaps this equation will help. Here, υ represents the volume of a given ingredient, ρ represents the fractional ABV, and Λ represents the total volume of the batch.

Take a classic cocktail, the Mexican Firing Squad, as an example. Although this cocktail is too simple to bother batching at my bar, for purposes of illustration, let’s calculate a batch recipe and make sure the ABV is high enough to include the grenadine. A fairly typical recipe is 1½ oz silver tequila, ¾ oz grenadine, ¾ oz fresh lime juice, 5 dashes of Angostura bitters, and soda water. We want to include everything in the batch but the fresh lime juice and the soda water. So, a potential batch recipe would be 6 liters of silver tequila at 40% ABV, 3 liters of grenadine at 0% ABV, and 11.271 oz (roughly 333 mL of Angostura bitters) at 44.7% ABV. Plugging these figures into the formula above, the total batch ABV comes out to 27.3%.

Using my own criteria, I would not allow this batch to be used in my bar because it contains a fruit juice syrup and has an ABV under 30%. That’s why it’s good to check these things out.

I’ve turned the formula above into an online calculator as well. You can use it for any batch with up to six ingredients, any more than that and you’ll have to grab a calculator. I hope it helps you out!

Storing Batched Cocktails

We batch our cocktails in large, 6 gallon NSF-rated food service buckets with spouts. Once all the ingredients are combined, we stir the mixture for several minutes with a large, NSF-rated whisk to incorporate all the ingredients. Then the batches go into the walk-in cooler onto custom-built, NSF-rated shelving. Because all the ingredients are shelf stable, it’s not strictly necessary that we keep the batches chilled, but it’s an added precaution we’ve always taken. Once the batches are in the walk-in, it’s simple to fill up the batch bottles we keep in the wells with the built-in pour spouts in the buckets. The batch bottles in the service wells are cleaned after each shift and replaced once they are a month old (again, this is not strictly necessary since all ingredients are shelf stable, but it’s just another example of how we ensure that our guests are getting the freshest-possible cocktails.)

For most of the batches we construct, the various ingredients have similar enough relative densities that giving them a good stir when they are constructed is enough to ensure that the batch remains incorporated until the bucket is empty. But there are batches in which liquids with different specific gravities will settle (usually those batches that include a more viscous ingredient, like a syrup or a particularly dense liqueur). For those batches, I have a weekly line-item on our prep sheet to give them a thorough stir. This ensures that the batch is consistent throughout it’s entire duration. It only takes our barbacks five minutes a week and ensures that I never waste any part of a batch due to ingredient settling.

More Information on Batching

Although this post covers the whys and hows of batching cocktails, there is lots more information about batching you may find helpful. See the posts below for more batching-related content.

Batching Cocktails to Save Money (coming soon)

Batching Cocktails and Inventory (coming soon)

Final Thoughts

I’ll admit that when I first started managing a bar, I—like those three panelists critical of batching cocktails at the Bar Smart Advanced seminar I attended—was skeptical of including batched cocktails in my bar. I was concerned that guests would be critical of the practice and that my bartenders would feel less like the craftspeople they are. I have since realized that getting a balanced, delicious, and well-made cocktail quickly is far more important to our guests than ensuring that their bartenders consider themselves artists. And I have found that changing the culture of our bar away from one in which the bartenders feel the need to justify their self worth with displays of their expertise to one in which they are humble and focused solely on providing our guests with true hospitality, has made our bar more popular, our guests happier, and has made the job of our bartenders more rewarding—both in terms of their job satisfaction and in terms of the average size of their tips. I hope this rather long and technical post has been useful in helping you decide if batching cocktails is right for your bar, as well as demonstrating a few best practices on how to do so. Cheers!

Notes

1 Why 30%? I’ll admit this is a fairly arbitrary number. After all, many commercially bottled fruit liqueurs are sold with ABVs far lower than this (18-22% is fairly typical). But my bar is not a commercial bottling operation; my standards of cleanliness, though very high compared to your average commercial kitchen, cannot compare with the sanitation regimes of commercial bottling operations that are using high pressure and high heat to sanitize their bottles and equipment. So, I let the alcohol do the work of preservation for me. I decided on the 30% ABV figure many years ago and anecdotal experience has shown me that it works to keep my batches free from spoilage, keeps my cocktails tasting fresh, and keeps my guests safe and happy.